Render Unto Caesar: Preaching the Gospel in an Era of Christian Power by Matthew Taylor

Beauty and Resistance Day 15

If you are watching the response to the death of Charlie Kirk and you are trying to make sense of a funeral that was marked by forgiveness and calls to hate, vigils that turn into “White men fight back rallies” then you need to a walk down about 2000 years of history to understand the context in which the Gospel of Jesus Christ has always been preached. It has always been in opposition to the empires of this world. And

is your guide.The views and opinions expressed here are solely my own and do not represent those of my employer, any affiliated organization, or any institution with which I am associated.

His book, writing, and videos are clear, compelling and Christ-centered in the way that our world needs right now because some of us have only been thinking about Christian Nationalism and what I call White American Folk Religion for the last two weeks or ten years but the conversation started over 2000 years ago when the Gospel of Caesar was written. Check out this post, the video above and make sure to subscribe.

Render Unto Caesar: Preaching the Gospel in an Era of Christian Power

[Matthew delivered this sermon on September 25, 2025 at the chapel service for Emory’s Candler School of Theology. This was part of a conference on Pastoral Leadership in a Time of Christian Nationalism. You can watch the video below or read the text of the sermon or do both.

If you’ve hung around a seminary like this (as I have), you’ve probably heard that Mark’s Gospel is the first gospel. Of course, Matthew comes first in the ordering of our Bibles, but it’s pretty standard critical biblical scholarship to recognize that the Gospel of Mark was most likely written first (sometime in the late 60s or early 70s CE), and then Matthew and Luke built on top of Mark’s foundation to produce their own Gospels. The Gospel of John came later and had its own unique set of sources. If you really want to impress people at the cocktail party you can even throw around fancy phrases like: the theory of Marcan Priority. Isn’t this what we signed up to go to seminary for? To learn fancy phrases and smart Bible stuff?

But if your New Testament professors have taught you that Mark’s was the first gospel to be written, then you have been taught wrong. Mark’s was not the first gospel. Neither was Matthew’s nor Luke’s nor John’s. The first gospel, the original gospel, was the gospel of Caesar.

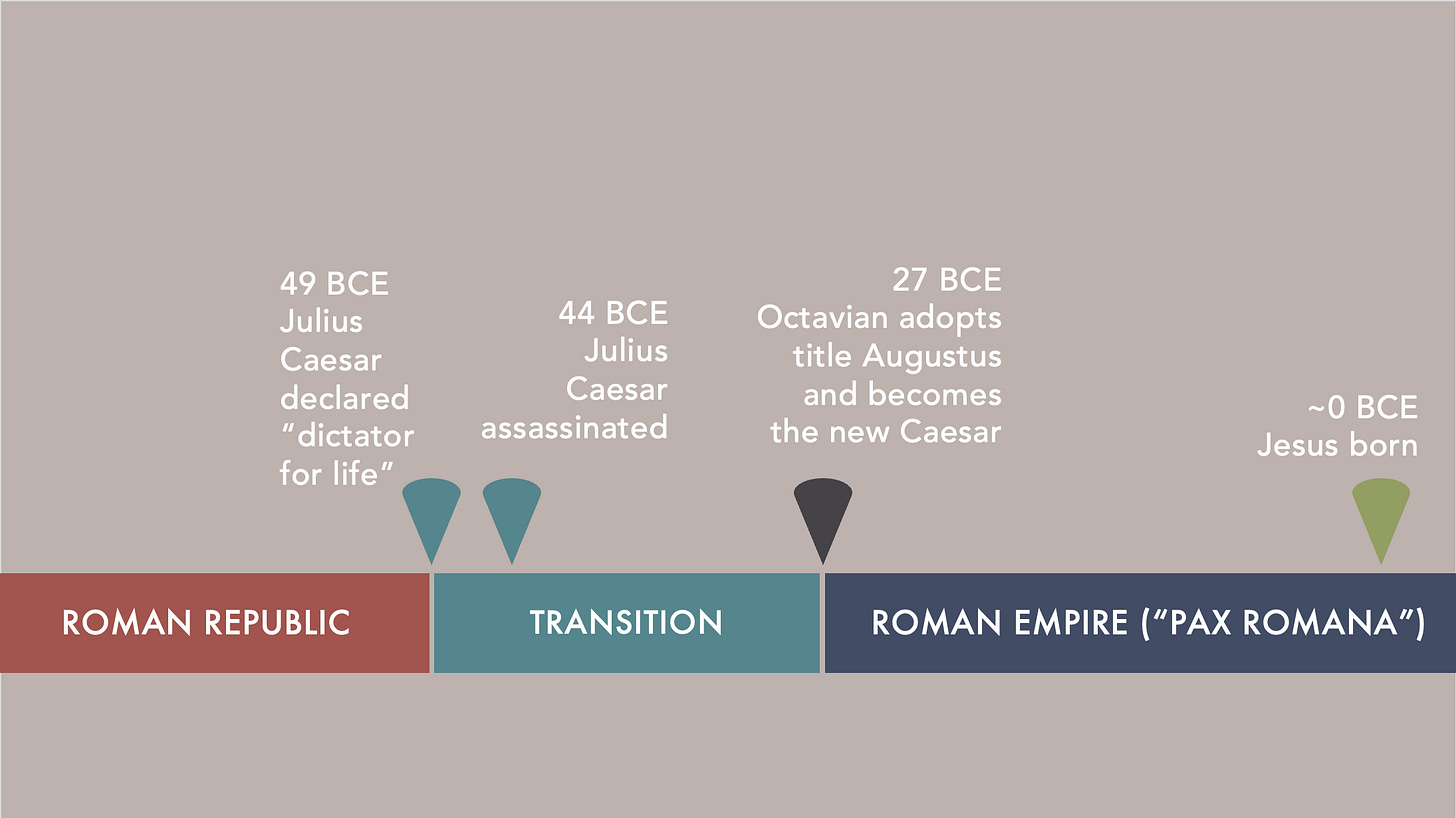

In case your Roman imperial history is a bit rusty, let’s do a quick recap. It was during Jesus’s grandparents’ time in 49 BCE that the Roman Republic fell and Julius Caesar crossed the River Rubicon and was declared dictator for life. But just a few years later, in 44 BCE, Julius was assassinated by his friends Brutus and Cassius.

Now after Julius’s death — if you remember your Shakespeare — two of Julius’s relatives, Octavian and Mark Antony tussled for control of the empire and both claimed the role of Caesar. Finally, Octavian, Julius’s great-nephew, consolidated power, around 27 BCE, probably right around the time that Jesus’s human father Joseph was being born. Octavian killed off all his rivals, adopted the title Augustus, and inaugurated the roughly two-century period of time known as the Pax Romana, the peace of Rome.

If all of this feels like distant history, long forgotten, in reality we are still living with the ghosts and the echoes of the early Roman Empire. In fact, it is currently September, and we just lived through the annual cycle of Julius and Augustus; our very months of July and August are named after the first two Roman dictators.

It was Augustus Caesar who wrote the first gospel. Predictably, it was about himself.

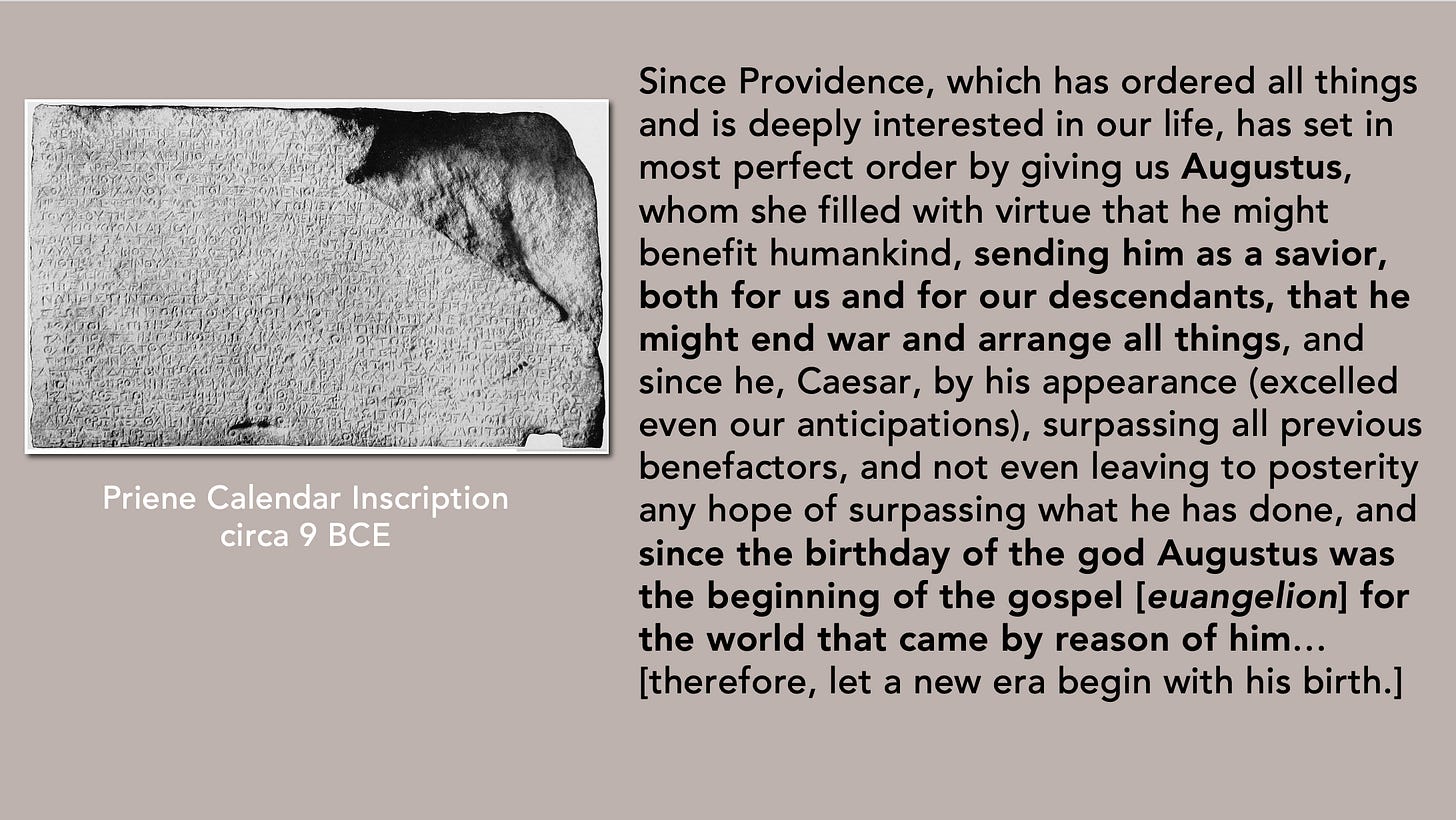

We know this, because archaeologists have unearthed a number of what are called “calendar inscriptions” that declare a new era beginning with Augustus’s birth. The most famous of these was found in a town called Priene in modern day Türkiye. Let me read that inscription to you.

(AHEM) A reading from the Holy Gospel, according to Augustus,

Since Providence, which has ordered all things and is deeply interested in our life, has set in most perfect order by giving us Augustus, whom she filled with virtue that he might benefit humankind, sending him as a savior, both for us and for our descendants, that he might end war and arrange all things, and since he, Caesar, by his appearance (excelled even our anticipations), surpassing all previous benefactors, and not even leaving to posterity any hope of surpassing what he has done, and since the birthday of the god Augustus was the beginning of the gospel [good news - euangelion] for the world that came by reason of him… [therefore let a new era begin with his birth].

This run-on sentence of imperial propaganda is the original gospel, the original euangelion.

Starting with Augustus, the Caesars began to claim that they were gods, sent by the hand of Providence to subdue and conquer the world. Caesar claimed to be a heaven-sent savior who would end all war. These calendar inscriptions help us see just how much of the early Christian vocabulary was already in use by Rome.

Make no mistake: the gospel of Caesar was a political message, but it was also religious. Very religious. In fact, beginning with Augustus, the subjects of the Roman Empire were required to bow and worship Caesar, their heavenly savior, a god who walks the earth.

Caesar’s gospel sounds a little bit like this (tell me if you’ve heard this before): Caesar is powerful, so Caesar must be in power through divine providence. He may not be a good man, but he’s the gods’ man.

The gospel of Caesar is that success proves virtue and violence brings peace. The gospel of Caesar is that domination proves divinity. Caesar is so far above the rest of us, sitting atop a pyramid of enslavement, ferocious politics, indiscriminate violence, and the mad scramble for power and status that was the Pax Romana, that he might as well be a god.

Anyone who refused to bow to Caesar and abide by Caesar’s new divine identity could be executed for defying heavenly tyrant.

The gospel of Caesar is what later Christian theologians would call “the divine right of kings,” the alignment of the regime of heaven with the regime on earth . . . Caesar’s kingdom come, Caesar’s will be done, in heaven as it is on earth.

This was the religious and political reality if you lived within the boundaries of the Roman Empire. And Caesar’s regime was brutal. Legions of Roman soldiers patrolled the colonies, arresting anyone who was suspected of dissent. Yanking them off the streets, willy nilly. Crucifying tens of thousands for daring to defy Caesar’s self-enriching order.

To sum up so far: we know that this Greek term euangelion, “gospel” was not plucked out of nowhere by the early Christians. It belonged to Caesar first.

So when we come to the first sentence of the first Christian gospel, the Gospel according to Mark, we have to realize what a revolutionary appropriation this was. We don’t know who the author “Mark” was, but they begin this anonymous text with a bold thesis statement.

Chapter 1, Verse 1

“The beginning of the good news (euangelion) of Jesus Christ, son of God.”

This isn’t even a complete sentence, but it’s a subversive challenge, a taunt even. The author is saying, in essence, “You occupants of the realm of Caesar, you’ve heard Caesar’s gospel, you’ve experienced Caesar’s domination. Now a different, non-dominating kind of king who is actually God’s son.”

Caesar has his “good tidings,” his “Pax Romana,” but I come with the gospel of a Jewish peasant whom Caesar crucified as an insurrectionist. That is the real God, the God who identifies with the lowest. This, I would argue, is Mark’s thesis statement: Jesus is the anti-Caesar.

If we had endless time this morning, I could walk you through the structure of Mark’s subversive argument, the perpetual contrast this rebellious author draws between the kingdom of Jesus and the kingdom of Caesar, but we don’t have such time so I’m going to focus us on these two passages from the latter half of Mark’s Gospel.

Mark builds the entire first Christian Gospel around a contrast and a building confrontation. Jesus teaches us about the kingdom of God, but Jesus’s kingdom is not like any human kingdom you’ve ever heard of.

Jesus’s kingdom is a secretive and small thing. It hides in nature parables and cryptic sayings. And Jesus’s confrontation with Caesar, particularly in the first half of Mark’s Gospel, tends to be centered on caring for the poor, the demonized, and the afflicted victims of empire. Jesus feeds hungry bellies, heals broken and ritually impure bodies, and frees the demonized from their torturing spirits.

But in the second half of Mark’s Gospel we see an inevitable crash approaching fast, as Jesus begins to anticipate and predict his confrontation with Caesar’s kingdom. Jesus teaches his disciples, a set of bumbling but loveable fools in Mark’s portrayal, that his path, and that of anyone who will follow him, is a path of suffering and self-denial.

Hence, in chapter 10, Jesus sees his disciples squabbling over who will be the greatest, who will have the most privileged place, and he rebukes them:

“You know that among the gentiles those whom they recognize as their rulers lord it over them, and their great ones are tyrants over them. 43 But it is not so among you; instead, whoever wishes to become great among you must be your servant, 44 and whoever wishes to be first among you must be slave of all. 45 For the Son of Man came not to be served but to serve and to give his life a ransom for many.”

We sometimes fail to note just how much Jesus is dissing Caesar in this passage. Part of the problem is that we read this with Jesus in our imagination being a Christian so when he says “among the gentiles” he must be speaking about all of humanity. No! Jesus wasn’t a Christian. Jesus was a Jew. When he said to his fellow Jews, don’t be like the gentiles, his nearest referent was the Romans, the colonizers, the kingdom of Caesar. When Jesus used the word “tyrant” to describe Caesar here, he was pointing directly to the greedy despot who was at the very top of the pile of domination, oligarchy, enslavement, and violence that was the so-called Pax Romana.

We could rephrase Jesus here as pointing to Caesar, the tyrant on his throne, and saying, “Do you want to be like him?!” Jesus’s whole kingdom of God concept is a reversal, and inversion of Caesar’s kingdom. If Caesar’s kingdom is a hill we climb, a mad scramble for power, then Jesus’s kingdom is a valley into which we descend by becoming servants, following our servant king.

Anyone who would try to sell you a gospel of Christian power, a gospel of Christian dominance, a gospel of Christian prosperity is not offering you the self-decentering gospel of Jesus. They’re just repackaging the gospel of Caesar in holier clothes.

This declaration by Jesus in chapter 10 that his kingdom is one of suffering, servanthood, and sacrifice, the antithesis of Caesar’s kingdom of domination, deceit, and deification — that is the essential context we must bring to our second passage, the only time in any of the Gospels that Jesus speaks Caesar’s name, the famous passage that we should “Render unto Caesar.” Or, if like the New Revised Standard Version, you prefer to make things less old-timey and poetic, “Give to Caesar the things that are Caesar’s and to God the things that are God’s.”

If you’ve been tracking this whole confrontation with Caesar in this gospel from Chapter 1, Verse 1, this passage should set alarm bells off in your head. The subterranean fight between Jesus and Caesar is now breaking into the open.

Here’s the setup: the Pharisees and the Herodians (strange bedfellows if you know anything about those two groups) are trying to entrap Jesus and so they ask him the unanswerable question for those who live under tyranny. “Is it lawful to pay taxes to Caesar or not? Should we pay them, or should we not?”

This is not a question about taxes. The question beneath the question is about empire and tyranny. If I might retranslate the Pharisees and Herodians: Will you cower before the commanding empire, acquiescing to their perpetual demands? Will you stand by while your people are unjustly policed and subjugated by soldiers on the streets? Or will you rebel, and risk the crackdown, and be killed?

This is the question that confronts all people who face tyranny, worldly powers and oligarchs and wannabe tyrants who are stripping away their rights and their safety day by day. Do we resist? And, if so, how?

This is a very dangerous question to ask, and it’s an even more dangerous question to answer.

Jesus, as is his wont, sidesteps the question. Jesus zigs when they expect him to zag. They are asking the question in the frame of Caesar’s kingdom: who dominates whom? But Jesus answers the question in the frame of God’s kingdom: whom will you serve?

Jesus asks them to bring him a denarius. The denarius was a Roman coin worth about a day’s wages for an average laborer, so maybe like a $100 bill today. I’m sure many of you well-educated seminarians could recite the exchange with me:

Then Jesus said to them, “Whose head is this and whose title?” They answered, “Caesar’s.” Jesus said to them, “Give to Caesar the things that are Caesar’s and to God the things that are God’s.”

If you think this passage is about taxes, you’re missing the point entirely. Both of the questions Jesus asks about the coin, the denarius, are important. He asks: “Whose head is this and whose title?”

The Greek word for head here, is eikon E-I-K-O-N, from which we get the English icon I-C-O-N. Eikon means image, likeness. In fact, in the Septuagint (you know you’re getting some fancy Bible knowledge when someone name-drops the Septuagint), the Greek translation of the Old Testament that was popular in Jesus’s time, the word eikon was used to translate that most important passage about human identity in all of the Hebrew Bible, the imago dei. Genesis 1, we are all, all humans, all of humanity, created in the image of God, the eikon of God. Jesus asks them whose eikon is on the coin. We’ll come back to that…

The second question Jesus asks is “whose title?” is on the denarius. Now this inscription is actually very important, and we know this because people have found a hell of a lot of Roman denarii, so we know what these coins looked like. What was written in the denarii was not merely Caesar’s name, no, these coins, like our modern coins, had a head’s side (the eikon side) and the tails side, where there was usually an inscription.

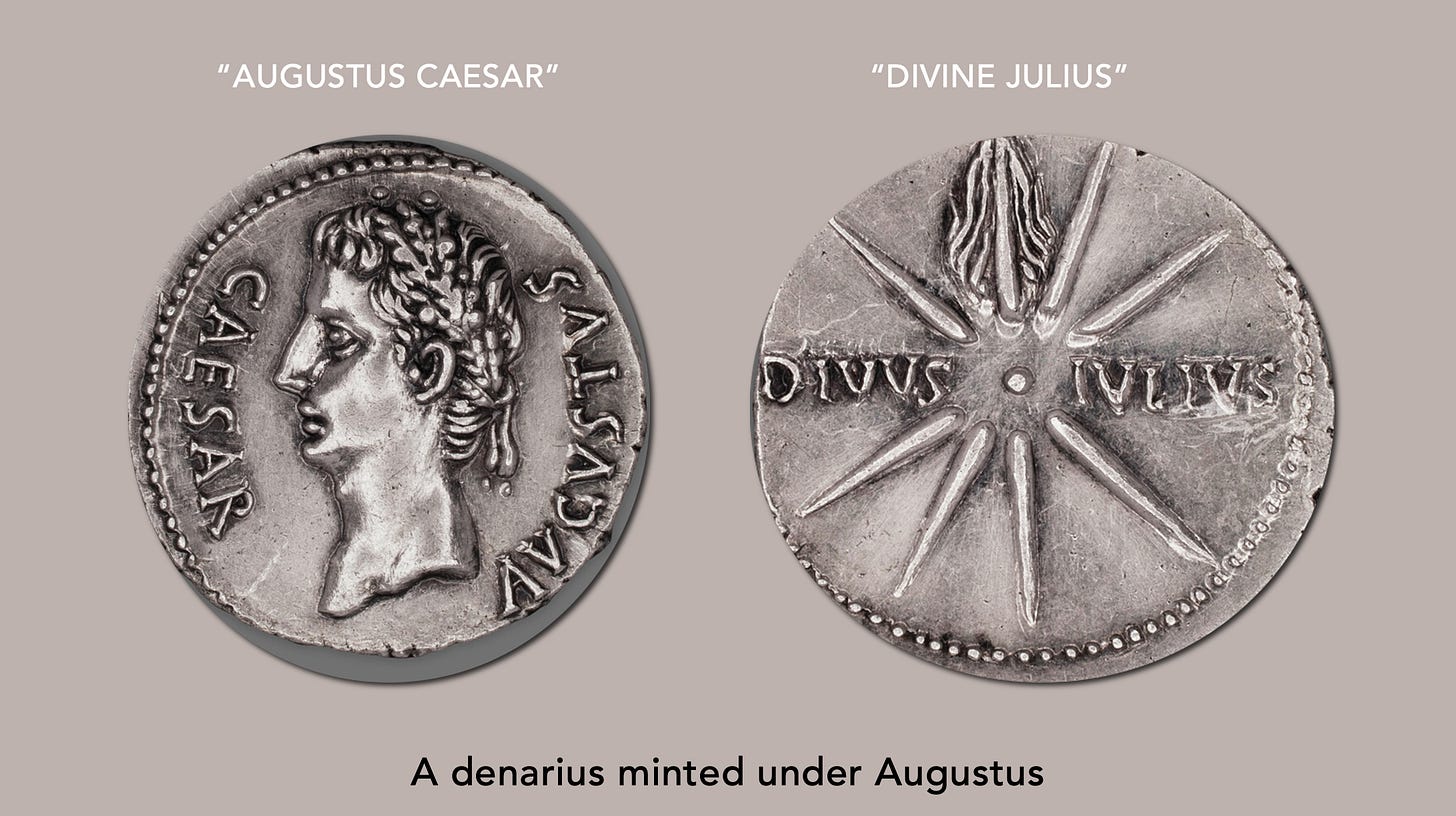

The inscriptions we find on the denarii held the Gospel of Caesar in miniature. Consider this example from early in Augustus reign, just as the practice of worshipping Caesar was getting under way:

You see, on the one side it says CAESAR AVGVSTVS (Esteemed Caesar) and on the other side there’s a comet with the inscription DIVVS IVLIVS (Divine Julius).

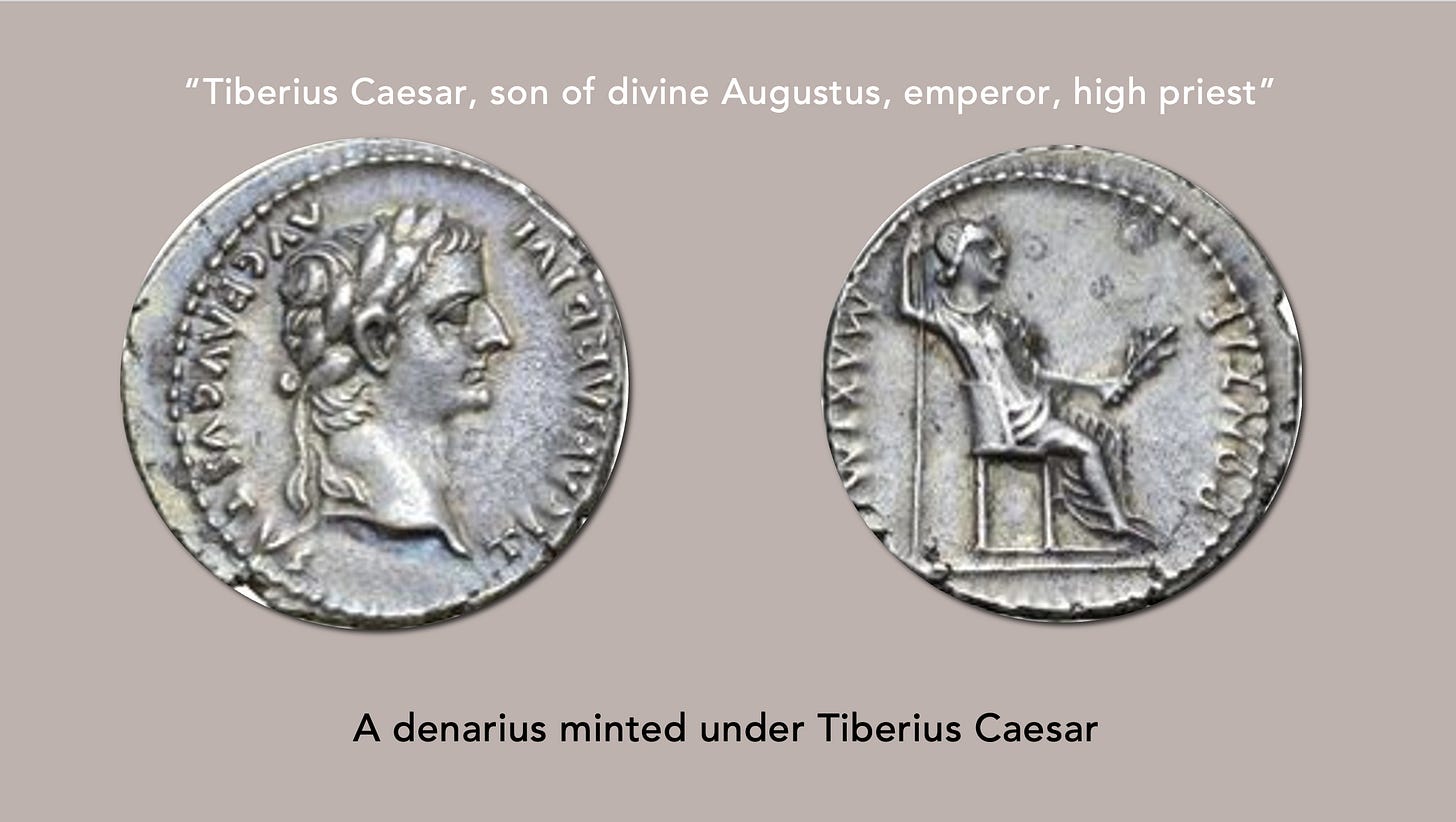

Or what about this one of Tiberius’s denarii (he was Caesar when Jesus was crucified) that similarly invokes Augustus’s divinity, casting Tiberius as the devoted high priest of Augustus’s cult, “Tiberius Caesar, son of divine Augustus, emperor, high priest.”

Jesus is not merely asking the Pharisees and Herodians to identify a coin. He’s asking them to reflect on the deeper reality. The denarius was not merely a coin, it was a token of empire, the Gospel of Caesar minted on a silver coin, propaganda of Caesar’s domination.

I would translate Jesus’s famous saying here of “Render unto Caesar” as really saying, “Caesar? You mean the narcissist who puts his face on everything he can brand? Put Caesar back in his place. He may rule you, dominate you, tax you, steal your money through tariffs and whimsical promises; he may crucify you, but he is no god. He’s just another tin-pot tyrant.”

Let us not forget that, a few days after Jesus said this, Caesar crucified Jesus. Crucifixion was the death of an insurrectionist. Jesus didn’t dodge the Pharisees and Herodians’ question. He raised the stakes.

But here we come back to that Greek word eikon. How easily we forget the rest of Jesus’s statement: “Give to Caesar the things that are Caesar’s and to God the things that are God’s.” If the coins are made in the image, the eikon of Caesar, then humanity carries the eikōn of God.

I take Jesus’s broader point to be: Yes, we all are hopelessly enmeshed in the kingdoms of this world. We will be taxed, beaten, commodified, conscripted, and colonized. Caesar may have his cross, his whip, his sword, and his taxation, but Caesar has no claim on me. The me that is in God’s image does not cower before your implements of war and weapons of desecration. They may flay my body and torture my flesh, but they chip and shatter on the indestructible image of God within me.

But we are also entrusted with the sacred duty of the innocent child in the fable of the emperor’s new clothes: pointing out the naked truth. We can pierce the veil of imperial pageantry and human hierarchies and proclaim that the emperor is just a self-deceived fool and a narcissistic tyrant. Beneath all his pomp and frippery and titles and delusions of grandeur, Caesar is just a human being, acting in a way that is nakedly inhumane.

This is the way of self-denial and suffering that Jesus teaches his disciples in the second half of Mark: we can defy the lords of the gentiles (Caesar and his sycophants and toadies) by living humanely, humanly from the margins of society by a set of values that thwart the very premise of Caesar’s power. Sometimes the most powerful thing you can do, when you have no political power, is to live by a set of values and principles that exposes the lie of the empire.

And yet… these values of a Christianity lived at the margins that we find in the early church… What are we to do with them in a situation where Christians are now the overwhelming majority? We have a declaredly Christian president, a bombastically Christian congress, and a dogmatically Christian supreme court. Nowadays, Caesar is Christian. Very Christian. Intimidatingly Christian.

Go back and read your history books: the blending of Christianity and empire (so-called Christendom – though I don’t think there was ever much Christ in it) Christendom has been one of the most destructive and devastating forces in human history. It led to enslavement, colonization, crusades, inquisitions, pogroms, and even genocides. And all around us we hear our fellow Christians clamoring for a new Christendom. A revival of Christian empowerment.

I submit to you that this is the theological crisis of our time: The clothing of the imperial gospel of Caesar in the meek garments of the gospel of Jesus. They proclaim that Christianity’s dominance over society will be society’s liberation, they are spewing forth Caesar’s propaganda.

Here in one of the great centers of theological learning of the United States, I declare that we need a full-spectrum, an all-hands-on-deck, an every-pulpit-in-America recovery of the gospel of powerlessness and marginality. We need to call out these false gospels of Christian empowerment, and remind all of these carnival barkers of Christendom of the crucified and colonized God we follow. We need to preach Christian dis-empowerment!

They are crowning Caesar with a crown of thorns and they are justifying abuse of innocent migrants, children, the least of these in the name of Jesus. If you claim to be a person committed to the gospel of Jesus and that doesn’t make your blood boil(!), then I don’t know what to do with you.

We need a theological renaissance, a Christian resistance to tyranny built around the subversive gospel of Jesus. Make no mistake: No one else is going to save us from this theological crisis. So we need a theological renaissance built around the subversive gospel of Jesus. We need it now. We are the people who can do that.

What will you do to be a part of that?

Amen.

Let me know what you think! I look forward to the conversation and comments because our screens make us into lonely consumers but God made us to be a vibrant, liberative community.

In Christ and for His Glory,

jonathan

I believe that this is the best piece I've read from your work. It makes very clear what we are up against.